Redefining masculinity: How Rick Morton and Corey White have thrown out the rule book

Rick Morton and Corey White are a part of a new school of Australian male writers. Between smoke breaks, these wise-cracking 30-somethings are redefining masculinity without shying away from it. In 100 Years of Dirt and The Prettiest Horse in the Glue Factory, Morton and White are honest about their shortcomings, exploring issues of drug dependency, self-harm, mental health and anger management. Where so many male writers tackling toxic masculinity have died on the hill of moral absolution, Morton and white talk about when they fucked up. They aren’t saints. they’re humans. Their vulnerability is essential in destigmatising weakness, in creating a therapeutic dialogue about masculinity, and all the bastards that come with it.

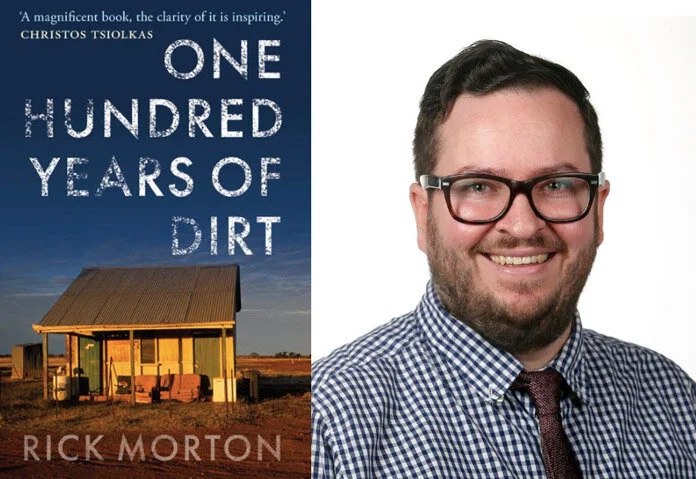

So rich with philosophical and socio–cultural history, 100 Years of Dirt, Morton’s debut memoir, is cerebral and emotionally charged. His deft transitions from the universal to the intimate give him the grace to negotiate his families’ complex relationship with land, trauma, class and male violence. George, Morton’s grandfather, once the owner of a cattle station reported to be the size of Belgium, was a callous and cruel man. Isolation emboldened his abuse. despite hating George, Rodney, Morton’s father, was cut from the same cloth. At age 7, Morton walked in on his father having an affair. His mum, Deb, was away at the time nursing his brother, Tony, who had been rushed to hospital after being severely burnt. On her return, Rodney left Deb. For years, he refused to pay child support. Deb, the unrewarded hero of this memoir, struggled to keep the family afloat. Tony, developing an ice addiction, began to mirror his father’s violence.

It would be reductionist to label 100 Years of Dirt as a search for forgiveness. While Morton shows a great deal of compassion for his father, his work speaks to the traumatic culture inherent to traditional masculinity.

“To understand a person you must understand his father. This is true of Rodney and it is true of myself, too. Ours is a trauma passed from one generation to another, family heirlooms bequeathed by the living. ”

Morton makes it clear that his issues with intimacy and self-love are inter-generational. He knows his father has suffered. Vulnerability is a new way forward, a subversion of violence that speaks to a common humanity.

In humanising his father, he rejects a cruel linage, and he assumes responsibility for his life.

“Of course I still love dad, but I don’t know why.”

Corey White’s The Prettiest Horse in the Glue Factory similarly explores intergenerational trauma in the scope of male violence. From a young age, Corey was witness to his dad’s horrific abuse. When Corey’s mum died of an overdose, his dad ended up in prison. Corey, lodged in the foster system, was the victim of sexual and psychological mistreatment. Believing education was his out, Corey compulsively studied, earning himself a spot at an elite private school. There, social humiliation was routine. Feeling out-classed at university, Corey turned to drugs and sex for escape, debasing his body in ways reminiscent of Bukowski.

Corey isn’t interested in self-aggrandisement or blame. Instead, he’s deeply philosophical and brutally honest. For some sons of DV, there’s the ever present fear of becoming the father.

“It took me being stripped of my humanity for me to gain humanity. Without this, I think I would have become my father. ”

Corey’s taken great care illustrating his pain, but he doesn’t weaponise it, nor assume a pretence of sainthood. Like Morton, he can still see the shadow of his father looming over him.

“I was not a good partner… I had a severe inability to regulate my own emotions.”

Both Morton and White are didactic writers who have discarded male affectation to make room for emotional intelligence. In literature, it’s hardly revolutionary for a male protagonist to have a difficult relationship with his father, nor his masculinity. These writers show us that real change begins by expressing pain with truth and vulnerability.

Further essential Australian writing on toxic masculinity:

On Drugs by Chris Fleming

See what you made me do by Jess Hill

Night Games by Anna Krien

The Lost Arabs by Omar Sakr

Invisible Boys by Holden Sheppard